In a previous post, I described what it is like as an Alberta Métis to come to Quebec and realise that ‘Métis’ does not mean the same thing here. I’m not a shut-in…I realised that there were different definitions out there, I simply hadn’t lived where I was defined by them before.

In another post, I talked about Pan-Indianism, and also Pan-Métisism. What this post and those previous two have in common, is that they are about identity.

The topic of Status was a much easier discussion, because I avoided delving into identity issues in order to give you the bare bones legislative context. Trust me, there are much larger identity discussions yet to be had on ‘who is an Indian’. More important, I’d argue, than just knowing the state of the categories right now…but you have to start from somewhere!

However, there is no real legislative context I can focus on when discussing who we are as Métis. I’ve no choice but to get all ‘identity’ on you. This is probably going to leave you with more questions than answers, but I do hope that your perception of the question itself will have shifted.

If I have any academic readers, I apologise in advance for bringing up debates or issues that some academics think are settled, or should be moved past. Whether or not I agree, the fact is that most Canadians have not been a part of these mostly internal discussions.

So? Is it your mom or your dad who’s the Indian?

I want to go into the history of the Métis, and talk about Powley and quote some John Ralston Saul (okay I actually have no desire to do that last thing) but this person just asked me a question at a party and his eyes are already drifting over the lithe form of a single neighbour. I have a hard time not addressing this question so sometimes we don’t get to be linear.

So I say, a little challengingly “neither. My mom is Métis”. I’m willing to leave it there.

His eyes snap back and he’s got a skeptical look on his face, “Oh,” he says, sounding disappointed and perhaps a little triumphant to have found a fake, “so you’re like, a quarter Indian?”

I am impressed with your mathematical skills, imaginary pastiche of all the people who have asked me this question since I moved to Quebec, but no.

And here I have run up against the little ‘m’ versus big ‘M’ identity argument. (I warned some of you I’d be rehashing supposedly ‘old’ territory!)

Little ‘m’? Big ‘M’? Huh?

If you were to boil down common approaches to Métis identity, you generally end up with two categories, sometimes overlapping, sometimes entirely separate, sometimes with all sorts of anomalies left over and scattered about. You, my egg-nog drinking friend who thinks it’s appropriate to quiz me on my ‘background’ are using the little ‘m’ definition.

Little ‘m’ métis is essentially an ethnic category. This is the category I’ve encountered most in Quebec. As an ethnic category, one is little ‘m’ métis when they are not fully Indian or non-aboriginal.

Obviously the Métis began as métis. (Funny fact, the pronunciation of Métis as ‘may-TEA’ is often seen as the proper French way to say it, but the French actually pronounce it ‘may-TISS’.) This is not the only term that was used, we were also called half-bloods, half-breeds, michif, bois brûlé, chicot, country-born, mixed bloods, and so on. My blogger name reflects that history, as âpihtawikosisân literally means ‘half-son’ in Cree.

On one extreme of little ‘m’ métis identity, one must actually be half First Nations and half not. On the other extreme, one can be métis with only a minimal amount of First Nations blood. You can just imagine the range of arguments involved in deciding where along the spectrum of ‘blood quantum’ is supposedly legitimate.

There are also discussion about connection to culture as a métis, so it is not always focused on blood. However, the cultural connection referred to is generally First Nations culture, not a distinct métis culture. This leads us into the big ‘M’ discussion. Do you want more rum in that eggnog?

Big ‘M’ Métis tends to be a cultural definition, referring to the blend of First Nations and European cultures resulting in the genesis of a new identity. There is less focus on ethnicity, although kinship ties are very much present. One extreme considers only the Red River Métis and their descendants to be ‘real’ Métis. Others consider any community to be Métis where it was founded by métis who developed their own culture and shared a history. On this extreme end you could imagine emerging Métis communities, not just historical ones.

So who is really Métis?

You mean, what is the definition I use for myself and thus present as the definition all others must live by? Oh come on, are any identity issues that easily navigated, even on an individual level?

Yes I am going to get personal, because it’s important that you know where I come from so that you understand why I have the opinions I have, and why others from different backgrounds may agree with me or not. I am going to ‘get personal’ so that people cannot effectively twist my words later and use them to deny others who feel that they too are Métis. I am going to speak for myself, not for all Métis peoples.

My understanding of my Métis identity has shifted considerably over the years. You see, I was only about 5 years old when the term Métis was recognised officially in section 35(2) of the Constitution Act of 1982. I point this out because although the term Métis predates that official recognition, it was not necessarily the most common term in use. Often we were referred to in the Prairies as the Road Allowance People. The term ‘halfbreed‘ still got tossed around a lot when I was growing up and was pretty ubiquitous in my parent’s and grandparent’s time. You can imagine how confusing it is in terms of forming an identity, to be known by so many ill-defined names.

What I knew but did not understand, is that we were related to pretty much everyone in Alberta, lots of people in Saskatchewan and a bunch of people in northern BC. Some of our relations lived on Stoney reserves, others lived on Cree reserves, still others had farms near places like Keephills, Smokey Lake, Rivière Qui Barre and so on. Names like L’Hirondelle, Loyer, Callihoo (spelled a million different ways), Belcourt…those were a dead give away that someone was related to me somehow. But aside from the odd family story that didn’t interest me as a child (but fascinate me now as an adult), I knew very little about our regional history.

So when I stopped being ashamed (a longer story there) and started to feel a part of something bigger, I turned towards the concept of a Métis national identity. That is when I started learning about a larger history than my own poorly understood, ‘boring-anyway’ regional one. Lots of talk about how distinct from European settler culture and First Nations culture the Métis are, with our own language (Michif mostly), our own style of music and dance, our own flag, our unique decorative style, our own symbols like the sash and the Red River cart. Heady stuff after generations of stories of ill-use, prejudice and shame.

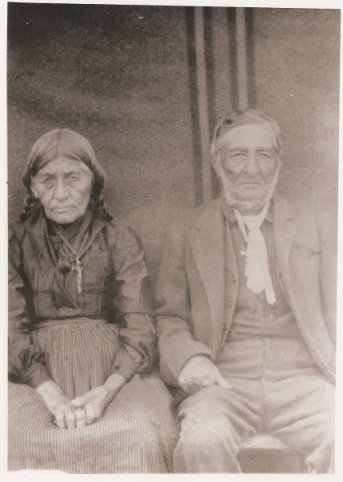

I still consider all those things important, and I appreciate the fact that the name Louis Riel no longer refers just to ‘some French guy who the English killed’. However, the history of my region…the history so many Alberta Métis share, is equally as amazing and rich and worth learning about. Take this photo for example. Angelique Callihoo was the daughter of Louis Kwarakwante Callihoo, a Mohawk fur trader, and his second wife Marie Patenaude. Almost every Alberta Métis can tie themselves to Louis Kwarakwante somehow through their family lines! Louis Divertissant Loyer was the son of Louis Loyer (original, I know) and Louise Genevieve Jasper.

Essentially there were just a few families that settled in Alberta and founded a number of Métis communities. The history of these families is a major part of the history of Alberta, yet I never learned about it in school. In fact, I’m still learning about it, and it becomes more fascinating and interesting with each new detail. My identity as a Métis person is linked to my family history, and the history of the community of Lac Ste. Anne in particular.

Dude, I still don’t get it, just how Indian are you?

*sigh* I have no idea. That’s not the point. My Métis ancestors intermarried with one another over generations, linking me to so many different Métis families that I tend to great most Alberta Métis as ‘cousin’. As do many of us, which never ceases to make my partner laugh.

Some of us look very ‘Indian’. Some of us have blonde hair and dark skin with green eyes…some of us like myself are very pale and can ‘pass’ as non-native. Some of us are nearly ‘purebloods’ if you insist on blood quantum definitions, and others are clearly ‘mixed’. What links us is our history, and our present sense of kinship and community.

We aren’t Red River Métis (though many of us do have links), we are our own Métis, Lac Ste. Anne Métis, Settlement Métis, Smokey Lake Métis, St. Albert Métis and so on…a history of settlement, movement, intermarriage, cultural growth, roots dug deep. Some of us are closer to our Cree and Stoney relations than others. We all have our own ideas about what it means to be Métis based on our lived experiences down the years.

This isn’t helpful at all, surely there is some definition you can explain?

Sure, but you aren’t going to like it.

You should be asking yourself why it even matters that you have a definition for us. As pointed out in that link, the concept that the Métis have some (as yet ill-defined amorphous) rights has a whole lot of people asking this question.

Well it wasn’t until 2003 that the question got some serious attention. The Supreme Court of Canada heard a case involving a father and son who shot a moose out of season and without a license. Exciting stuff, no? No!? Well…it turned out to be exciting. For the first time, it gave us a basic legal definition besides half-Indian, half-European to discuss.

The Powley Test as it’s now called set out basic criteria for determining who is Métis. Here I am using the Métis Nation of Alberta’s summary of those criteria, which is pretty similar to what other regional Métis organisations have adopted and use to determine regional membership:

“Métis means a person who self-identifies as a Métis, is distinct from other aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, and is accepted by the Métis Nation.”

Egads! So much in there to unpack and debate! So many more questions than answers! A little bit of ‘calling yourself Métis is good enough’, with some ‘have to have First Nations blood in there somewhere’ and whole lot of ‘other people have to agree that I’m Métis’.

Then there is that whole, ‘distinct from other aboriginal peoples’ part that so baffles the many Cree-Métis and other First Nations-Métis mixtures out there. You can be one or the other legally, but not both! That would be double-dipping…or something.

Sounds confusing.

It is, but what identity issues are simple? I’m going to quote a rather long passage here by Chris Andersen because I think it’s important to keep parts of this passage in its fuller context or else I run the risk of making some people feel attacked.

When I argue for the drawing of boundaries around Métis identity to reflect a commitment to recognizing our nationhood, however, colleagues often object, as many of you might, in one of two ways. The first objection usually takes the form of a challenge rooted firmly in racialization: “If someone wants to self-identify as Métis, who are you to suggest they can’t? Why do you think you own the term Métis?” I ask them to imagine raising a similar challenge to, say, a Blackfoot person about the right of someone born and raised, and with ancestors born and raised, in Nova Scotia or Labrador, to declare a Blackfoot identity because they could not gain recognition as Mi’kmaq or Inuit. Second, I am sometimes asked, “What of those Indigenous people who have, due to their mixed ancestry and the discriminatory provisions of the Indian Act, been dispossessed from their First Nations community? What happens to them if we prevent the possibility of their declaring a Métis identity (some of whom, due to complex historical kinship relations, might legitimately claim one)?”

Such disquiet is often buoyed by a broader question of fundamental justice: What obligation, do any of us – Métis included – owe dispossessed Indigenous individuals, and even communities, who forward claims using a Métis identity based not on a connection to Métis national roots but because it seems like the only possible option? Whatever we imagine a fair response to look like, it must account for the fact that “Métis” refers to a nation with membership codes that deserve to be respected. We are not a soup kitchen for those disenfranchised by past and present Canadian Indian policy and, as such, although we should sympathize with those who bear the brunt of this particular form of dispossession, we cannot do so at expense of eviscerating our identity.

I admit that I do tend towards the more inclusive definitions. I believe in dual citizenship so to speak (even triple or quadruple citizenship!). However I also understand where Andersen is coming from, and I tend to agree. My ‘inclusive definitions’ are still big ‘M’ definitions.

At the same time, I chafe at the necessity of playing this game at all, where our identities and our rights continue to be defined by the Canadian courts and the Canadian state. This is an issue that plagues all native peoples so I’m not going to whine about it too much here in the specific Métis context.

I’ve got more questions than answers, what am I supposed to do with that?

You could start with learning more about the history of the Métis, which of course means also learning more about the history of First Nations and the interactions and relationships with European settlers that shaped this country.

This is a good resource, for example, though it is loooooong! It covers many periods and also includes the author’s particular views on the Métis identity, so keep that in mind. Now you know a little about those different views, which will certainly help you navigate the wealth of information out there. Keep in mind too the regional variations in history that you will encounter…there is a reason I refer to us as Métis peoples. You can also read some of the books I linked to above for both contemporary and historical views. Essentially, you can be interested, and like any topic you are interested in, you can start digging.

Most of all, remember this. If you ask anyone who they are and what it means to be that person, you’re not going to get a clear-cut simple answer. Do not assume that the lack of a clear-cut summary means the person you are talking to doesn’t know who they are. Don’t assume that having a nice clear definition makes things simpler.

Being is a verb, it’s a process. Being Métis is something you can spend a lifetime trying to understand. Most of us just live it, however, and when we do reflect on it, we don’t let it paralyse us.

I’m glad we had this discussion, I hope you enjoy your holidays!

Thanks! You have written what I could never quite clearly express about my Métis identity and my ancestry. Miigwech and merci beaucoup. Happy Holidays to you too!

Thank you for your view. While I myself do not identify as Métis, your points evoke similar feelings with my own mélange of culture.

I think perceptions may change as more becomes public through genealogical research, which has become so simple that almost anyone now can determine ancestry pretty far into the past. There was always a tradition of Indian blood in our family, but no evidence that passed to our generation. However recent research has given us names and dates that confirm a French and Onondaga mix that ultimately spawned some of the pioneers who moved west and founded the Red River settlement as well as others who stayed in and near Quebec.

Would you consider this ancestry to be a part of your family history, or a part of its present identity?

It’s unquestionably a part of family history. As to present identity, both prior to and since the history was uncovered, a proclivity toward involvement with native culture was clearly evident in a brother, who made it the focus of his academic career, and in daughters who have embraced the northern frontier and (a) partnered with a full-blood Cree; (b) adopted an Inuit child. Recently, I’ve been writing about it. Still, it’s a big family and there are many other communities of interest. I would say we are Canadian to the core and reinforced in that identity by our discovery of Metis heritage. As a corollary, I’d suggest that many are becoming aware of ancestral Metis and First Nations connections due to enhanced record search capabilities and that this enhancement of awareness and understanding presents an opportunity to enlarge the circle

I appreciate your response to what can sometimes be seen as a challenging question. I am trying not to trigger defensiveness in people because I have seen it rear up in so many situations, and legitimately so!

What you are saying about rediscovery and the easier ability to engage in that process is interesting to me, because most certainly I have seen this in my own situation as well. There is a lot about our regional history, for example, that was forgotten or thought irrelevant. And because it wasn’t taught in school, it became even more difficult to access. Delving into family and regional history used to be extremely difficult. Mining older people’s memories and trying to piece together fragments contributed by other family members…even 15 years ago this was an exciting but extremely frustrating exercise. So many pieces missing. So many questions left unanswered. So few resources to access. Hints! A name in a journal or a paper, the names misspelled but birthdates correct and so on. Now, with the work so many people have put into this, there are more accessible records, and more of us can compare what we have learned. It’s truly amazing.

But my real point here is this…there are people who will be very critical of those who did not grow up in a Métis community. Since acceptance and recognition by a historical community is now part of the legal Métis identity, there is a lot of pressure to be ‘choosy’. I get that. There are people who would claim only the name in the mistaken belief that this would get them some sort of benefits (pardon me while I chuckle as I consider what ‘benefits’ Métis have available to us). It’s offensive to be used that way, I feel it too.

However, there are many who upon learning more about their family, really delve into it in a respectful and earnest manner. Just like there are First Nations individuals who were cut off from their community and family for so many reasons, and have to struggle to regain some sense of their First Nations identity. I think it’s no less valid for Métis individuals to engage in this. Forget the legal definitions…our communities are pretty good at figuring out who is there to exploit and who is there because they mean it.

Anyway, a bit of a ramble there 🙂

It never occurred to me that there was anything to exploit in being recognized as Metis, nor am I inclined to seek approbation from an historical community. As I understand the four part definition of Metis identity, I qualify on three of four counts and that’s good enough for me. I did look into what is required to gain acceptance by an historical community and found that the paper trail they would have one lay down would challenge the greatest of genealogical scouts. I don’t blame them for setting a high hurdle. I’ve just figured the connection recently and am at least two generations removed from any physical connection to a First Nations community. On the other hand, I share ancestry with Lagimodiere, Gaboury and Riel, so I feel a certain justification in self-identifying, wearing the sash, showing the flag (red or blue) from time to time, and encouraging discussion of issues that I’m just starting to be educated about. I hope this is not considered exploitive by anyone.

Thanks a bunch for this article and the links – much appreciated.

Best of the holidays to you too!

I love the mix of thoughtful analysis and chatty tone on this blog. I’m learning answers to questions I never even knew to ask. Thank-you.

LOVE LOVE LOVE!! Have you ever thought about Métis politics?? We need a strong Métis leader in Alberta, one that will stand up for us when President Clem Chartier and the eastern Métis try and cram their sash’s and Michif down our throats (strong words, but yes, I believe that’s what has happened to me.)

I was chosen as one of 25 Metis youth chosen from across Canada to attend a conference hosted by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the MNC. Don’t get me wrong, that conference was life-changing and I’m so thankful to have been given the opportunity for learning, however….

I don`t speak Michif and no one in my family does. I had never known the history of the sash until I attended this gathering. I never knew the ins and outs of Gabriel Dumont. I actually left that 4 day gathering thinking to myself, I must not be a TRUE Metis…I mean, how could I be if I do not know about these things?

It seems that the MNC chooses to ignore the fact that Metis living in Alberta have a distinct history from the Metis of eastern Canada. Because Mr. Chartier is a lawyer, he understands that to have land rights, hunting rights and the rights of a distinct minority, Metis need to have an official language (Michif) and distinct culture. He’s got his eyes on the prize, and that is aquiring assets for the Metis people at all costs (including siding with the unjust former Peavine council earlier this year, but that’s a whole ‘nother discussion). So with the allowance of the rest of the MNC, he has developed a framework and a definition of what a Metis person SHOULD be in regards to their traditions and language. I believe this has happened without adequate input from our western Metis reps.

A little bit about myself: My grandfather is Metis and my grandmother is Status Indian. So subsequently, I had the choice to be Metis or Bill C3. Lucky me, some might say, because people before me fought very hard battles for me to have this choice. However, my point is this and it’s what I presented this to Mr. Chartier in a letter earlier this year: Why must we choose? I am both. Same as a child born of an American and a Canadian can apply to be a dual citizen, why can we not have a dual citizenship within our own country?

From my grandfathers side: I jig along to fiddle tunes, I play spoons, I’ve attended many a kitchen party, I’ve felt the discrimination and the confusion as to being sometimes too “Indian” and sometimes not “Indian” enough. On the other side, my grandmother is on the C&C of a northern reserve, and we use traditional medicines to pray and heal. I’ve been to medicine men and ceremonies. I’ve learned First Nation values, and I’ve begun learning Cree. How can I choose which identity I hold more dear to my heart, when I am BOTH.

Mr. Chartier’s reply at the time was that he leads in a way that represents the majority. He stated that he polled the Metis Nation of MANITOBA (ha! case in point) and they voted against the idea of dual citizenship. I’d really be interested in seeing how that poll would play out here in Alberta.

Anyway. I wanted to thank you for this post. Since attending the youth conference in Batoche, I now have Metis friends from across Canada, and I know some of them are the leaders of tomorrow. I hope they will read your post and understand where we as western Metis come from, and why it doesn’t make me any “less” Metis.

The thought of going into any kind of politics gives me hives! Despite the delightful internal bickering that goes on within any group, I think the MNA does a good job of advocating for our particular histories. Focusing less on pursing hunting test cases in court, and more on capacity building and education would be a nice shift for the MNA but that’s going to take pressure from membership in the province.

I understand what you’re saying about doubting whether you pass muster as Métis when confronted with super Métis nationalism. My way of dealing with that was to pay more attention to my family’s history and the history of our region. I can accept the sash and the flag as national symbols. Red River history is important to us too, because of how the entire situation impacted federal and provincial policy towards all Métis. It helps explain why so many people went ‘undercover’ after 1886.

For me, the trick is in recognising that we have regional variations as Métis peoples, much in the same way that there are regional divisions among non-native Canadians. The history of Newfoundland, for example, is quite different from that of Alberta. The national history of Canada needs to reflect that better than it does, to be honest, but there is at least a recognition that regional differences can be quite vast and actually help shape the national character. I believe there is room for that within a Métis national identity as well.

The problem is that we aren’t aware enough of the regional differences yet. That is going to take people in the various regions rediscovering and teaching their history and the differences that exist. I understand that some people believe we need to be careful with that sort of thing because we must remain ‘distinct’ (from First Nations and Europeans) or risk not being a rights bearing community…but if we try too hard to fit into the Powley mold, I think we risk losing our histories as younger generations learn only about the Red River.

I definitely agree that Western Métis have not had enough input into the discussion of Métis identity. I wonder how much of that has to do with the fact that so many of us have grown up as I described…first just ‘being’ Métis without much awareness of how to define it, then exposed to the national Métis identity? Without digging, it can be an easy identity to accept even if you feel uneasy and left out. Taking the time to really evaluate why you feel uneasy and left out is difficult when you’re paying attention to living your life. Not all of us have the time or space to do that kind of thinking.

I am not going to panic, however…I think we are very much at the beginning of a journey, no matter how it seems that we must finalise a definition now for all time. I don’t care how we all end up being ‘defined’. It won’t change history, it won’t change my kinship ties.

I think Michif is worth revitalising and I would even support its spread to communities that do not necessarily have a strong history of its use…as long as I did not have to ignore my own Cree language in the process in the name of being ‘distinct’. There are Michif speakers in Alberta (though some of them will insist they are speaking Cree 😀 ). Our histories are rooted in multilingualism.

We will have to address dual-citizenship at some point. There are so, so many Cree-Métis and other First Nations-Métis mixes. Right now, you are forced to choose a legal identity…you’re either First Nations or Métis, and not both. Of course this does not change your dual identity…but it can interfere with aspects of it when that legal identity is conflated with real identity. If you have people excluding you because you ‘chose’ one legal identity over the other, then there is a problem. I see that as another example of divide and conquer. Yes, it would be complicated to figure out what rights could be exercised by which people when they hold ‘dual-citizenship’…but it would not be impossible. We’re all scrabbling after an ever-diminishing ‘pie of rights’ baked by Canada, wherein taking a slice for yourself means removing a slice from someone else. The whole thing is set up to divide us and make it impossible to work in solidarity with one another as aboriginal peoples.

I too would be interested in how Alberta Métis would react to the idea of dual-citizenship.

In terms of having other Métis understand where we come from, and who we are, I think the best thing to do is to continue to tell our stories to one another. Hmmm. That would be a cool project, wouldn’t it? Some sort of website for Métis to connect and share stories and so on? How I wish I was more technical minded!

Thank you so much for your thoughtful post. It’s really important I think to know that other people are thinking similar things, and have similar questions. I have found that it makes me feel more certain that who I am and where I come from is relevant.

Finally, someone who explains this well. I get so many questions on how Metis or Aboriginal I am. Thank you for this article.

hey homie – great article. You have a very welcoming writing style (far more so than mine!). If you are interested, I have some stuff around ‘peoplehood’ that pushes the ‘big M’ Metis discussion a bit farther than I think it has been…having said that, You seem to have a pretty good handle on these issues already…

Tan’si Chris:) If you have any suggestions for further reading on the big M issues (especially that could be read online), it would certainly be welcome so people can pursue it if they are interested!

Thank you for hosting such an intelligent discussion on a subject that many of us don’t really talk to others about. I’m starting the discussion in my own family by sending links to your blog to my siblings.Don’t know how interested they will be…will be interesting to find out!

I like what Tony said in an earlier post: “I would say we are Canadian to the core.”

Here’s what I’d like to share. From 1990 to 1995, I lived in Mexico with my husband and our young son. Almost EVERYBODY there was of mixed blood–mestizo! I felt so much at home, especially because my mother’s ancestry is Spanish. Learning Spanish in Mexico gave me a link to her ancestors–one that was severed when her parents decided that voluntary assimilation into Canadian culture was the way to go during the 20th century. My mom does not speak Spanish, although she heard it being spoken when she was a child in Sudbury, Ontario.

Learning bits of Ojibwe from the songs we sing at a women’s drum circle in Ottawa links me to that part of my ancestry. I’m happy to have these ways of relating to my ancestors. The personal becomes political! Looking at my great grandmother’s photograph (the Ojibwe link to a First Nations’ community in Ontario), I know that her blood is strong. I see my father in her face, and his sisters, too. Having the freedom to understand and explore all of who I am makes me immensely rich.

Being firmly planted in this land we call Canada is such a glorious thing. I missed Canada terribly when I lived in Mexico. I missed the clean air, the cold lake water on a summer day, the smell of the pine trees in northern Ontario. If I could have one Christmas wish it would be that the type of apartheid that the Canadian government has perpetrated against aboriginal peoples would end. It’s time to unravel that pattern of oppression. May strong leaders from the aboriginal community emerge to take on that task. May the shining examples of resilience that exist in so many healing and healed First Nations communities be our guiding light. And may the voices of the women be heard so that the children will know the path home.

Love it! (As usual cousin). I will be happy when the question is not asked any longer. How insulting it is to hear my least favorite question in the world “so…what IS a Metis, anyway?” Has anyone ever heard anyone ask: “what is an Irish?” “what is a Cree?” “What is a chinese?” “what IS an Ojibway anyway?” why do the people asking the question about who we are not realize the question itself is insulting. I’m working on a painting right now fueled by this very subject. so, again thank you so much for writing your thoughts…can’t wait till the next blog post!

Very nice. We halfbreeds have to stick together. Wait…

😉

Love the blog. I thought i was a one time visitor but I keep coming back for more.

Unrelated, I took a peak at the I Am A Warrior poster….love!!!! I may have to order one when I’m no longer so seasonally cash-strapped!

The definition of metis being a person who is accepted through their participation seems to be similar to the Australian aboriginal. The big ‘A’ aboriginal is someone who participates in the culture and community but may be able to ‘pass’ as white.

Having grown up as an “Alberta half-breed:, being recognized as Metis for 45 years and then moving to Manitoba and being told for 15 years that I wasn’t Metis because I wasn’t from the Red River Valley, it was a joyful experience to come back to my home province where WE know where we came from, who our families were and how we lived. We didn’t need to wrap our selves in a sash and fly the Metis flag to show just how Metis we were. We just WERE. We lived the life, passed on our stories, raised our children to be proud of who they are. Thank you my girl for putting out those good words, in a good way. I too think that you would be a fine voice for Alberta Metis. Your logic and way of saying the important things in such a good way would cause the Clem Chartiers and David Chartrands of the old boys network to hang their heads.

To be honest, hearing stories like these, I’m pretty happy I was so insulated from Red River purism. What I wasn’t insulated from was the question of whether Métis are legitimately aboriginal or not…but what was so interesting about that was the people asking these questions were First Nations people from the east mostly. (I’m talking internal discussions mind you, not discussions with non-natives) Some of the people who were the most staunch defenders of the Métis-as-aboriginal-peoples were First Nations people from Alberta! These were in person discussions at conferences, or on-line discussions btw.

Obviously the historical and cultural contexts are different depending on the region you come from. I have yet to meet an FN from northern Alberta or NWT or the Yukon who was not very familiar with the Métis (which makes sense given how intermarried we are). So I didn’t get challenged about being Métis very often. When it did happen, it was often on a blood quantum level…a discussion that I think may be more common in the east?

Anyway. I have only once experienced someone claiming I couldn’t possibly be Métis since my family is so rooted in Alberta. To that sort of thing you just have to assume that the people making such claims don’t understand our context.

Fantastic post and coincidentally an issue I’ve been dealing with! There is another side to this “blood percentage” story I’d like to touch on, if I may. After learning about my own Metis ancestry, I set off on a journey of self-discovery that resulted in the creation of art work that I was able to exhibit and speak about at a number of cultural centers/galleries. Each and every time, I was confronted with two types of people: those who were or were married to Metis (and therefore understood what I was talking about), and those who had never really heard of the “term” other than a vague memory about some short-lived rebellion. I live in southern Ontario and our grade/high school education didn’t really include much about First Nations history at all let alone Metis history so probably why there was so little recognition among those who didn’t know what a Metis was, regardless of big M or little m. What I find interesting though, is that scholars now claim that 40-60% (!!!!) of French Canadian families in Ontario and Quebec can easily trace First Nations ancestry within their lineage, hence technically making them Metis if you consider the “blood” aspect. I don’t know about you but I find that astounding. What I find even MORE astounding is that if there are so many people in Ontario and Quebec with First Nations/Metis ancestry, why aren’t we teaching/leaning about Metis history and the Metis experience of Ontario and Quebec as well? Why have I had the impression that if you weren’t from Manitoba, Saskatchewan or Alberta, you couldn’t possibly be part of the Metis club? (This question isn’t being asked to put anyone on the defensive but rather an honest-to-goodness desire to know why the Metis experience seems to have been made irrelevant in these provinces.) My own Metis lineage began in the 1600s in Trois Rivieres when an ancester married a Mi’kmaq woman. That was just the first instance of several mixed-marriages in the line but the point is that none of my ancestors continued the westward migration beyond northern Ontario. Still today, the majority of my fam live around the Sudbury area, speak a form of Michif (which I used to call a twisted Frenglish before I knew what Michif was), all practice some cultural form of artistic expression that is distinctly Metis when you look at/listen to it, are avid hunters/trappers and display many — if not all — of the distinct traits we learn about from the Red River/Saskatechewan Metis as naturally as if they had come back from the west. In a sense, I feel robbed that some academics or beaurocrats or who-have-you have denied me my family’s history. It annoys me to have to defend myself about my identity let alone take a bunch of time to re-educate people on Canada’s accurate social history. I feel – and am – just as Metis as a Riel or Dumont even though my family never lived west of North Bay – except for the odd temporary stray. All that said, I appreciate that you are reopening the identity discussion. (And you do it so completely articulately and eloquently!) I’m sure I’m not the only Ontario Metis who feels that it’s high time our ancestors were counted in Canadian history books. We are proud to be Ontario Metis, proud to be a part of an important heritage and want to be included within the definition (if we MUST have one). Finally… thanks for providing me the opportunity to rant about it.

What an interesting discussion. I am Metis from both my mother and father’s side, and trace my paternal family lineage back to 1640s (does that make me more Metis??). I have just earned my PhD at the University of Calgary where I based my dissertation work on working with the community members from the Fishing Lake Metis Settlement (my home community) in collecting collaborative narratives from youth-Elder pairings on stories of survival.

In fact, when our primary blogger admonishes: “In terms of having other Métis understand where we come from, and who we are, I think the best thing to do is to continue to tell our stories to one another. Hmmm. That would be a cool project, wouldn’t it? Some sort of website for Métis to connect and share stories and so on? How I wish I was more technical minded!” — I was compelled to respond, “But we have.” The 19 digital stories (3-5 mins long) are so amazing so I am so looking forward to the day when the Fishing Lake folks are ready to share them.

That is awesome! Can’t wait until the project is available! Please update us!

My ggg grandmother hailed from Wisconsin, and in her later teens journeyed with her kin up the Great Lakes to N. Ontario where they eventually settled in Ojibway territory. En-route they wintered in Grand Marais Minnesota where it was arranged for her to marry a French fur trader upon reaching their destination in Ontario. They married and brought my gg grandmother into this world who in turn married an Ojibway man. Then came the birth of my grandmother who birthed my father out of wedlock. She was enfranchised at that time and later married a French man which doubly sealed her fate in the scheme of no longer being considered ‘Indian’ by definition of the Indian Act and no longer entitled to treaty rights.

I identify with my early ancestors, our old people’s oral history and my identify as Metis. Bill C3 restores my father’s full status from his previous sub-full status position, and now affords my sibs and I with sub-full status (mother is non-native), nontheless my identification is firmly rooted in my relations with my first kin. Makes sense to me, however not so much to some others no doubt. Dual citizen indeed! Thank you for stirring the pot, and keep the fire burning!

Thanks you again for the links – very encouraging!

http://telusplanet.net/dgarneau/metis.htm

I was too young when Bill C-31 passed to see the upheaval directly after, though the ripples of that have not yet subsided. The consequences of Bill C-3 aren’t very visible yet. I think it is making a lot of people reexamine categories. The fact that so many First Nations in Alberta (and elsewhere) became ‘Métis’ arbitrarily has muddied the identity waters so much too. Michel’s Band, for example, is a prime example of that. You’ve got Status Indians, and a push to enfranchise everyone, with some members of families taking scrip and becoming ‘Métis’ (literally in some cases siblings from the same family ending up on opposite sides of the identity line)…then all the remaining Status Indians losing Status involuntarily, and then back to having Status.

So there was enormous outside pressure on which ‘identity’ you were able to exercise. If because of that your family became culturally Métis (or culturally First Nations, which also happened after Bill C-31), then do you stick with the ‘old’ or the ‘new’ identity when given the choice?

These are hard, personal questions, and I think everyone who is faced with this will have to answer those questions for themselves. Bill C-3 is going to create more conflict in our communities, as Bill C-31 did…and people fought for that, and I’m glad these changes were made…but having so much external pressure still being put on deciding ‘who belongs’ really skews the entire issue. Deconstructing that to get at ‘real identity’ might not even be possible anymore. Our identities are indelibly marked by the machinations of the Canadian state. I think that point can never be forgotten when we discuss identity.

I agree apihtawikosisan.

Sadly Bill C-31 created real conflict and C-3 will undoubtedly do the same.

My ‘real identity’ is no less than who I am – truly the sum of all of my aboriginal and non-aboriginal parts. That is not debatable at the heart of my ‘real identity’, although the Canadian state’s definition of my ‘real identity’ is imo incongruent and divisive. I agree that this point cannot be forgotten in the course of this discussion – unfortunately.

âpihtawikosisân, I was reading through your older blog entries and came upon the “what my children learn in school”, and it reminded me both of my own education and story. One of my family members was born in North Africa. They are of European lineage, but they were educated along side the local arabic population. Now, the school was based on European culture and history, but my family member recalls all the members of the class having to recite that “my ancestors had blue eyes and blond hair …”, even though that the arabic locals hadn’t shared that history.

Now, I’m not knowledgeable on Metis history (but I’m starting to learn) — but it would never have crossed my mind to ask a person of Metis identification about their parents in this way.

Anyways, thanks again for a fantastic and thought-provoking piece.

Reblogged this on So Far From Heaven.

Morehistory , You seem to be the exception in these parts. Because of termination legislation and a severe inferiority complex within the Metis community itself, we have become quiet content on allowing others to inform us as to whether or not we are Metis! A whittling away of our identity, a cultural anomaly that has created difference’s on both sides of this “Identity Line”. It would seem that our entire identity is in question. A question of authenticity and verification. By those who haven’t the first clue as to what Metis is.

The only reason we are having this conversation is because the Canadian government has taken it upon themselves (via the “Treaty” or “Status Card”)( as apposed to “Script” or land as it were. To be traded, sold, or cultivated and forgotten into the Canadian fabric) to be able to tell how many Indian’s are actually left. And this has only transcended towards the Metis condition. And a certain protectionism has developed among many non-Aboriginal Canadians in fear of even more “Claims” whether it be land or sovereignty. Only this time by the Metis! Who love to ask the question ” So how much Indian do you have in you anyway?”.

I am not an Indian. I am Metis. Like my Father and my Grandfather. And my Great Grandfather and his Father. You see this could go on for another generation or two for all anybody knows. The Metis have been a “Distinct People” for many generations now. It’s time we stop confusing Aboriginal politics with the Metis identity. and start to figure out what it means to be Metis in a modern canadian context.

What did the Metis do for Canada?

Maybe this is more the question we are after.

Tim

The Metis represent in their persons the Canadian ideal. Here’s a story. My first European ancestor born in Canada was Anne Mouflet, who was among those taken by the Iroquois in their invasion of Lachine in August 1689. She was released and in 1697 married René Tsihène, an Onondagan. They were not wed in Nouvelle France. The marriage took place in Iroquoisie. These two were both in the thick of it in August 1689, on opposite sides, his people killing her people, and terrifying her. But survival in harsh conditions — conditions could get harsh indeed in 17th century North America — require a practical turn of mind. After a while the hurts healed. Cooler counsels prevailed. No more war. War no more. Peace. In 1701 the great peace treaty of Montreal was signed by Governor Hector Callière and the chiefs of all the Amerindian nations of the Great Lakes region. Anne and René weren’t the first mixed marriage between white and aboriginal although it was early in the origins of the distinct Métis population in Canada. Most of the unions that produced the 400,000 Canadian Métis alive today began in the 18th and 19th centuries, between Algonquin, Cree, Ojibway or Mi’kmaq women and Canadien voyageurs and Scottish traders on their travels east and west from Montréal. But René Tsihène was the man of Anne’s house. It must have worked well enough. After a few centuries, every genealogical list reveals dozens more cousins from the same stock. Unusual it was for her to be Canadienne and he Onondaga. How much more unusual that they had set aside the hate from the day of infamy when they had been on opposite sides. Despite furious provocation, this early willingness to “bury the hatchet” — Callière and the Chiefs threw war-axes irretrievably into a “pit so deep that no-one could find them” as a symbol of good faith before the Great Peace meeting of 1701 — has become, after germinating all these centuries, a quasi-genetic Canadian trait to consult, to compromise, to accept and welcome different peoples, to mix, to keep the peace. That’s my opinion. The fact is that out of the ashes of Lachine Anne and René began to populate the nation that in time would become Canada. I reckon 1/1,024th of me flows directly from these two. There are probably more links to First Nations and Métis to be found. But even if this is the all of it, it’s enough. It’s starter for a unique breed that gains strength from diversity.

While I understand what you’re trying to get at, I do find that the language suggests that the original ‘breeds’ were somehow weak. The whole discussion of ‘breeds’ and ‘stock’ doesn’t sit very well to be honest.

The language doesn’t suggest anything of the sort unless you bring a preconceived interpretation to it. I understand that someone who has been called a half-breed might be offended by my use of the word breed. If that’s the case, I apologize. But If the discussion hangs up on words that are in common and non-pejorative use to describe genealogical relations of human beings, I don’t have the patience to pursue. It’s been interesting to participate. I think the work you’re doing is very useful.

‘halfbreed’ is still used at the Museum of Man in Ottawa for ya’ll. I actually think the problem Métis people have with the term may not actually be etymological but actually other associations with the word.

‘halfbreed’ is often used (especially historically) to describe someone who is shifty, cheating, sneaking, or otherwise marginal. Societally, ‘halfbreeds’ exist on the edge – out in the shack in the woods with their illegitimate children, selling chopped wood for poverty wages or stealing what they need, etc., and getting dragged into court for ‘not properly feeding and clothing their offspring.’ I ought to know – ‘halfbreeds’ is what I come from. (And I’ve just described their actual lifestyle ca. 1900.) It now has been transformed into the more broad ‘white trash,’ I think.

The Métis, many of whom were/are devout catholics, etc., obviously take issue with this implication. They are not ‘marginal’ people. At least not anymore. It would be like calling them ‘road allowance people’ when they don’t live on the edges of roads, but rather in settlements or in major metropolitan areas.

Hi Tim,

Excuse the delay, I didn’t hit the checkbox to follow comments on this entry, and was just casually reading through the discussion when I saw your response.

Some of the problem that non-aboriginal people have is simple ignorance — the lack of education with regard to the history of Canada prior to settlers. When “chapter one” of your book starts when Europeans settlers show up, there is a lot of things lost. Also, the narrative of many books relegates aboriginals to support roles, and after Canada becomes “settled” the mention of Aboriginal people trails off.

Some of the issue is protectionism with regard to land claims, and a bunch more is the willful ignorance of treaties and “rights” not well explained, which have people believing that any money that goes to any Aboriginal group is a “hand out”.

I think some of it is the fact that the whole thing isn’t black and white. Like most things in life, there are lots of shades of grey, and it takes some time to learn about, process, and understand. It’s easier to stick to the preconceptions and prejudices, since they feel much more black and white.

I have more to say on this, but I need to indulge a little in the Holiday season. Happy Holiday time to all. 🙂

One thing that strikes me about these responses (intelligent responses as opposed to much of the dreck out there), is that very little of them are built in the context of discussions about attachment to a CONTEMPORARY Metis community. It’s become a genealogical discussion. But while genealogy in itself is an important component of claiming a Metis identity, it shouldn’t just be about genealogy (i.e. it is necessary but not sufficient). Otherwise, instead of working in concert to build a better collective future for Metis, we become mired in discussions about proving our (more or less authentic) connection to ancestors (again, without much discussion of which community/nation/people THEY were attached to). To make my own stance explicit, I have become a fairly hardcore Metis nationalist over the past decade of being in academia. To me, Metis identity was and is about a connection to some type of community (whether a nation, a people, or whatever). There are good reasons (both academic and otherwise) to prefer this stance to individualistic ones (and good reasons to prefer a link to a nation or people rather than a community, but I won’t go into them here) – suffice it to say here, they largely relate to avoiding the kind of voyeuristic “I am Metis” responses these discussions often turn into.

Of course, an immediate question that stems from this is “when do Metis people ‘start’?” For me, it’s not about the fur trade, or intermixing, etc. (again, necessary but not sufficient). Instead, I start where Metis self-consciousness arguably started – the Battle at Seven Oaks in 1816. All historical memories relating to nationalism are arbitrary but this seems as useful as any and more useful than many others. Lots of “intermixing” occurred in the upper Great Lakes but their status as “Metis” relates to their kinship connections to Red River (instead of mere intermixing). This is not to suggest they have to be FROM Red River or even ever had to have been IN Red River (in fact, most Metis spent most of their time away from that metropolitan core).

In (m)any other instances, people of these various kinds of intermixing were…well…whatever they called themselves. For example: Seminole Indians, Lumbee, Comanchee – are all ‘post-contact’ Indigenous peoples, the result of intermixing between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. That doesn’t make them Metis, anymore than people in the upper Great Lakes are ‘Metis’ as a result of their intermixing (as opposed to regional connections to Red River).

None of these kinds of conversations can be had in individualistic conversations about how “I” am Metis or how “I’ am related to so-and-so, who was the result of intermixing between so-and-so and so-and-so. People often complain about boundary making (as in, why do we need to define ourselves) – partly, this is because if we don’t, the state will: and their definitions have not been kind to our own definitions or ways of seeing the world.

That’s why I’m not so much interested in why individuals (think they) are Metis but rather, which community claims you, and why are THEY Metis?

I realize this isn’t a popular opinion and I don’t mean this in anyway to disrespect anyone. Just giving my two cents with respect to the brilliant blog post that Chelsea began this conversation with.

Fair points, and I’ve been deliberately avoiding pushing things in this direction, hoping it would go there itself, so woohoo!

Being ‘part of something bigger’ is where my political consciousness began and what made my specific family and community history more meaningful. Individual kinship ties keep me rooted in my individual identity. However, wider ties and connections to people from many different communities (historical and contemporary) and the similar goals and aspirations (not always apparent during the muddled in-fighting of politics) of the Métis (all of us as opposed to just us individually) is what moves us beyond just ‘family’ and into ‘nation’.

A nation does not have to be homogeneous, and there is space within a nation for regional differences. To me, being more aware of your regional history merely means that you have a richer tradition to draw on in order to address new issues as peoples, working together. There is a lot of resentment about Red River purism, but I think we could get beyond that fairly easily when we have those ‘national’ versus ‘individual’ discussions, so I’m glad you’ve brought this up. The history of the Red River is not an attack on individual identity, it is a socio-political context that is extremely relevant to discussions of nationhood.

But I’m interested in both discussions 😀

I agree with this and also with the moderator’s response. But what most interests me is the Métis as personification of a Canadian ideal. It’s not just the blood mix, but an interweaving of disparate cultures. It’s a core Canadian value.

I just see that approach going very badly. It made me cringe when J.R.Saul went on about this too.

Well it’s not meant in a way to make anyone cringe. I haven’t read Saul on this yet, though people tell me I should and I will.

Perhaps you could explain how the approach is going badly. In what way? Going badly for whom? Does it somehow make things worse?

I’ll come back to this later…too busy cooking these days to get too deeply into these subjects 😀

From my perspective, Tony (and it’s just a perspective), there’s two fundamental issues with multiculturalism discourses more generally. First, the part that the ‘multiculturalism’ discourse misses in a Canadian context is the tremendous amount of physical and symbolic violence enacted historically in order to produce it. That is, the Canadian state was able to expand west only on the territories (and in many cases, the lives) of those who lived and owned them before the expansion. Multiculturalism is based fundamentally on a tolerance of difference – whether linguistic, ‘visible’, etc. But that tolerance is only possible because the Canadian state destroyed the viable alternative polities that stood in its wake.

Secondly, making the argument that Metis (in particular) are “mixed” or multicultural in a way that all First Nations are not, flies in the face of about three hundred years of First Nation involvement in similar sets of social and economic relations to those of Metis. All First Nations today are equally the result of disparate cultures and yet, they aren’t hosted on the same petard as Metis are. Our ‘mixedness’, while celebrated at a very facile level, in effect delegitimizes our Indigeneity as merely ‘post-contact’ (and as such, not as authentic as those of First Nations).

Anyway, that’s my issue(s) with it.

Thank- you for writing this. When I first moved to Ottawa from northern Alberta, people (mostly FN) didn’t understand why I just wouldn’t identify as being First Nations. I have darker skin so no one ever said why don’t you just identify as being White. In any case – I realized that Many people “out east” understand Metis to be “wanna be” First Nation peoples. Although I admire and respect the diversity of First Nations in Ottawa – I am very much a Metis person. I’ve mostly enjoyed teaching people about Metis and I think that for those out there who are willing to share their thoughts on being Metis will solidify that “meaning” that we know to be true and accurate. ekosi.

This is a fascinating discussion. I wrote a paper about a similar topic last year and I’m so happy to read so many other perspectives on it. Chelsea, from now on, any time anyone asks me that question, I’m sending them to this article! Chris, have you written or published more about Metis identity lately? I’m a bit out of the ole UofA/FNS loop these days, but if you have, I would love to read it!

Hi Joyce,

I have but its mostly been on the idea of ‘peoplehood’ and why thinking about Metis collectivity in terms of peoplehood is preferable to ‘community’ or even ‘nation’. I can send you some articles if you give me an email address. They’re pretty academic, though – I don’t have Chelsea’s ability to explain complex concepts in non-academic language (I wish I did!).

Maybe you just haven’t had enough practice talking about this stuff in rural bars 😀

ha ha…i wish I had that excuse. I just got tired of translating for people who had no interest in learning. One of the truisms of colonialism is that non-Indigenous people can choose when and how they engage in relationships with Indigenous people – and those who continue to ‘engage’ through racism, ignorance and stereotypes simply bored me to the point where I now write for those I think I have a chance of swaying. But giving up isn’t the answer (obviously) and your blog has made me aware (again) of the hard work but the vital necessity of doing so.

This blog came after a very long bout of being fed up for exactly the reasons you’ve described. The energy it takes to ‘translate’ for people ebbs and flows…with more ebbing than flowing unfortunately. However, I find academic spaces to be nearly as hostile as non-academic spaces. Less obviously so at first, but perhaps also less honestly as well. I think my approach is a reaction to that, because I received the training too…I can max out the syllables and use jargon that excludes and pepper my writing with trite latin phrases, but colonialism is still colonialism regardless of which philosophical excuses are used to perpetuate it. I think I object to being forced to engage that kind of dialogue at all. So, like many things, my reaction is to be ornery and do it differently 😀

sing it, sister!

Hey Chris! I am just reading this reply for the first time here. I would love to read your articles! Email at joycenathan@gmail.com. I hope you are well!

Its 5:30am on Christmas eve and I really should be sleeping ha! Ha! Good morning. I’m just wondering what would happen if instead if Metis Nation we instead made the full and official switch to Michif Nation? I’m not advocating for that. Just that, for example, Ojibway language is Anishnaanemowin and people call themsleves Anishinaabe. My grandma conversed in Cree and Michif so my question here is not cut and dry, only wondering if It would be easier on me if I could just answer the questions I get with “I am Michif” .. “an Indigenous nation in Canada” …rather than trying to explain to those that dont understand that I am Metis who are from Metis who are from Metis who are from Metis. Ha ha! Just wondering. Would we cut down on confusion between big and small m convos? K gonna have some coffee. Hope all of your holidays are Merry.

Christi – interesting that you should suggest that – awhile ago, a Maori friend of mine (Indigenous person from New Zealand) were talking about writing an article on this exact issue! A lot of people suggest that Metis were first ‘metis’ (i.e. small m and big M) but I don’t necessarily agree (this isn’t a dig at you, Chelsea, this distinction is a very common way to understand the issues and makes it very simple). The ‘wrinkle’, of course, is that while people self-identified as ‘Metis’, i doubt their ancestors self identified as ‘metis’, first. Metis – as all identities – begins with self-consciousness. Metis versus metis is simply a category of analysis used by Jackie Peterson and Jennifer Brown in their New Peoples text (who took it from the MNC’s own original differentiation) – it doesn’t reflect actual categories of practice. And I think, whenever possible, its prefer to use actual automymity (a fancy word for self-identification or categories of practice).

Hence, when I’m in western Canada, I self-identify as Metis. When I am anyplace else, I self-identify as Michif. Again, I don’t mean to offend anyone, just my perspective!

That’s an important point about the difference between what people thought of themselves versus what other people categorised them as…and how those categories have shifted (and become retroactive) over time. We use terms now that were not necessarily in use ‘then’ nor had the same meanings as they now do. It can make historical investigations more confusing if we don’t take this into account, and more complicated if we do try to understand the shifting terms and identities over time.

Btw, Chris, I’d like to read those papers if you don’t mind! I’ll email you so you have my contact info.

Yeah ‘Métis’ confused the heffers out of me when I came to Cree studies in Canada all those years ago. As an American, I knew nothing about all this, because the American system worked hard to eliminate the possibility of ‘Métis’ existing as a ‘people.’ Australia worked hard at it, too, as I recall.

As I understand it, in the U.S., the categorization worked like this: If you were on reservation, you were an Indian. Hence, you were not counted on any census. If you were off, you were either (a) black or (b) white. Sometimes, they allow for a ‘mixed’ category of black/white. Usually marked M on the census. There was no recognition of any other group – under any circumstances.

Everybody got funneled into ‘white.’ I actually tracked the ‘whiteness’ of several of my family on censuses – it was entertaining. ‘Black’ in 1850, ‘Mestizo/Mixed’ in 1860, and ‘White’ in 1870. It had to do with how close they were to ‘white’ lifestyle, essentially. For a woman, marrying a ‘white’ male was a guaranteed ticket to ‘whiteness.’ For a man, it would take more time. The ‘black’ men in 1850 weren’t ‘white’ until 1900.

So, the funny thing is that, in most ways, my mother’s father’s family are classic ‘métis’ people. But there is no consciousness of that as a possible concept. Hence, they see themselves as ‘white.’ Just darker-skinned, rural whites who happened to do a bunch of weird things that white people didn’t generally do. Most ‘métis’ people in the U.S. got lumped with ‘white trash.’ Which is, I guess, what we all are. 🙂

I think the Canadian situation is actually really quite unique in the acknowledged existence of a Métis group. That’s largely thanks to Riel and Dumont and the rebellion, in my opinion. You guys earned an identity with your own blood. Hang onto it.

I’ve come back after a busy month to catch up on some apihtawikosisan, and I’m so glad I am!

I love this discussion. It is, for me, so Canadian. The good part. Discussion, acceptance, willing to have disagreements without stopping the conversation, our history, our present, our future. I can’t quite explain it, but I know I love it.

I have learned more in this one post about Metis peoples than anything schools have taught me. I always feel cheated of my country’s story when I learn how poorly it is taught. I only learned about Riel and the Red River Metis in school. Thank you all for continuing my education, I am thirsty for it

ha ha…someone more cynical than me might suggest, Moira, that it is typically Canadian, also, in the fact that we talk about it but do little or nothing concrete about it. 🙂

Tansi – I am coming into this conversation a little late as I see from the dates, however, what a pleasant suprise to see so many of my michif cousins (I like that word association, Christi) sharing views and making so much sense of this issue!

âpihtawikosisân – you are a wonderful writer and like one of the other comments here, this may be one of my first times to your site but it will not be the last. I am proud to say that your Blog will help move this confirmed Luddite (half-Lud?) into the 21st Century so thanks for that.

Although I live in Ottawa now, I am originally from the Edmonton area and growing up in the 1950’s and because this is Alberta we are talking about, I was definitely known as a half-breed. Hurtful at the time perhaps due to some of the more colourful invective also thrown in for good measure, but the term is one that I pretty comfortable with now actually. However, I am careful where I use it, in describing myself and will often use, “Je suis michif” in polite company 😉

You have given me more to chew on in regard to this issue so thank you for that!

Using ‘michif’ instead of ‘metisse’ (for myself) might be a good idea when talking to francophones. I think it would prevent the common misunderstanding of what I’m saying:)

Hi – perhaps I will discover references in other parts of your blog to the Lac Ste Anne pilgrimage, but since you grew up in the area, did you participate – either willingly or by force of nature – meaning usually a Mom or Grandma ;-)?

My grandmother, Louise Berard, would take me. And I have pretty vivid memories – visual, aural, smell, taste – of the time spent there. For example, the Cree / Michif women singing “Amazing Grace” in the church, in that high nasal way. Eating dry meat and bannock with lard in the smoky canvas tent. I could go on and on, but will not. But more curious about your experiences.

I finally got to go last year after two years away from home…I haven’t missed many years I’m happy to say:) It’s always awesome to see people you may not have seen since the last Pilgrimage, and the smell of the muddy grass and the smoke and the water and the constant music…yes. I think I posted some pictures in an earlier blog post…ah yes, here we go!

I’m usually there the day the Driftpile wagon train gets in, and when the Alexis and Paul Band pilgrims walk in barefoot. Last year it was so muddy I got my mom’s crappy truck stuck and when I finally got us out, I went back home and got her to drop us off instead.

Thanks! Now, THIS is identity.

Great photo’s as well – took me a minute to clue in on the priest’s buckskin vestment – very cool.

You mention the water, which of course is the primary significance of the place and that brings me one more memory of being my grandma’s little crutch as she waded into the water for cleansing and to retrieve small bottles of the holy water. I meanwhile being freaked out by the slimey weeds around my legs and imagining leeches – but hey, je suis michif, no matter how young, so no complaining!

Hahahha, my girls complain about the muddy sand and the seaweed too…sheltered 🙂

I have metis cousins in Alberta. I am a plains cree %100. I am from a reserve called Hobbema and when I told my metis cousins this, they never contacted me again, emabarassed to know a person from the Hobbema. Why is it the metis colonies in Alberta are bigger than the reserves and did the metis people consult the Indians if they could take their land? No, they asked the government and they gave it to them.

I’m Métis, and I know (and keep in contact with) people from Samson Cree and Ermineskin. I can’t speak to the actions of your cousins. As for the Settlements, this is the only landbase the Métis have, anywhere in Canada or the US. I have heard some people speak out in resentment against them (and against Métis people in general), but most of what I have heard is supportive of the Settlements, and it was hardly as easy as ‘asking and receiving’.

âpihtawikosisân — I agree totally with your last statement and I would urge Guide Fleury to read, “The One-and-a-Half Men” by Murray Dobbin. The book tells the story of Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris both of whom were instrumental in the establishment of “L’association des metis d’alberta et des territoires du nord ouest” which of course is the forerunner to the Metis Nation of Alberta Association, and also speaks to the establishment in 1934 of the Ewing Commission: An Inquiry into the Condition of the Half-Breed Population of Alberta. One of the outcomes of this commission was to set the stage for the creation of the Metis Settlements – Page 118+ for specific reference, but also Page 73+ for reference to the cooperation of key First Nation political leaders of the day, which goes to the heart of the criticism from Guide Fleury, I believe.

The book also talks about the other key figures at the time, including Pete Tomkins, Felix Calihoo and Joe Dion – collectively know as the Big Five for their activism and their wide sphere of influence. Malcolm Norris also helped to establish the Indian Association of Alberta, along with William Morin, Dan Minde, Albert Lightning, John Callihoo, Henry Lowhorn, Ben Calf Robe, Bob Crow Eagle, Dan Wildman, Sam Minde, Joe House and John Laurie. Many of these names are well known in Alberta.

And marcee Guide Fleury for the spark which will lead me to re-read this excellent tome.